法利赛人是谁,需要放在历史、神学与新约叙事中整体理解,而不是当作一个简单的贬义标签。

一、法利赛人的历史身份

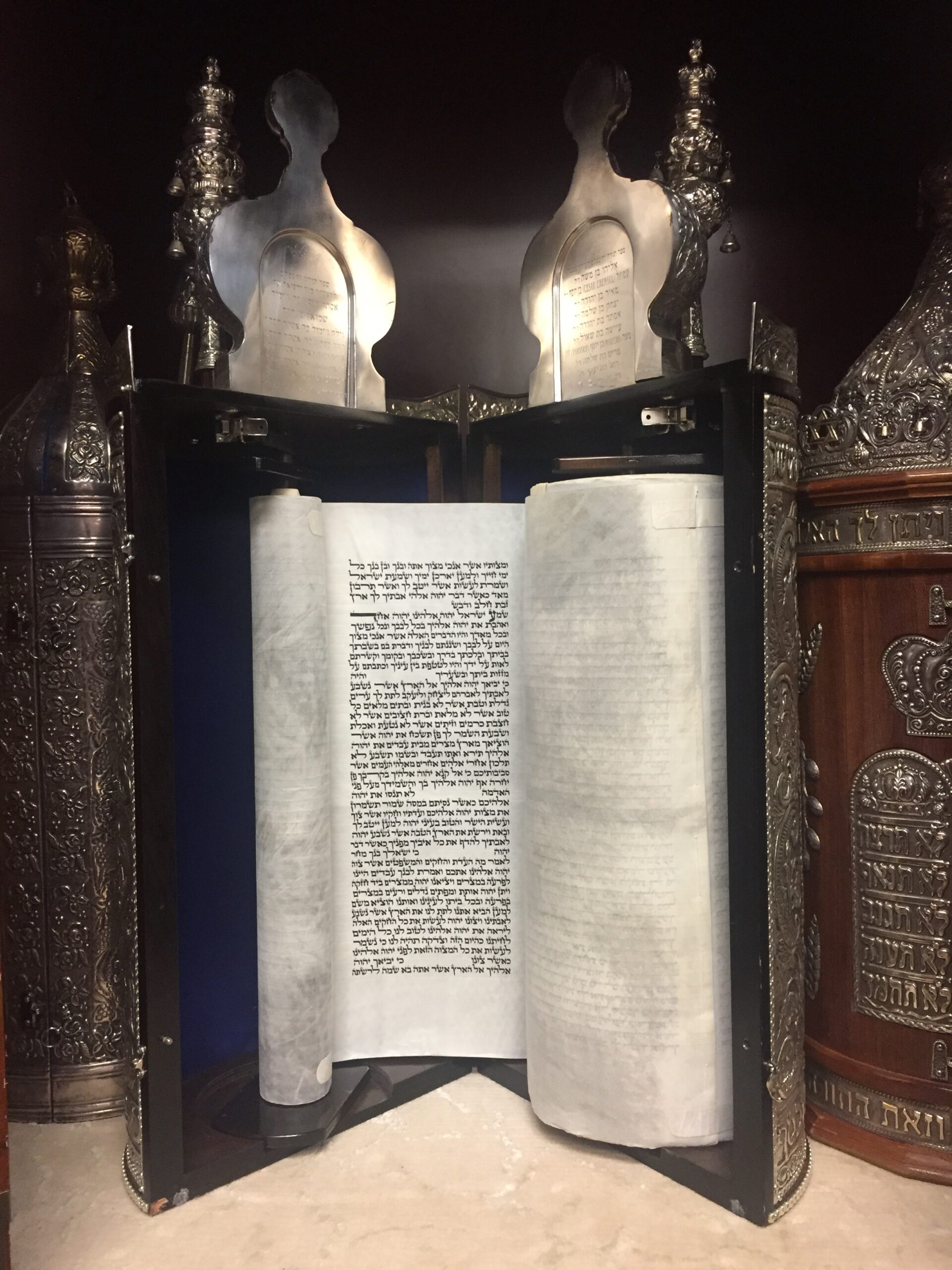

法利赛人是第二圣殿时期犹太教中的一支宗教群体,活跃于 主前2世纪 (BC) 至 主后1世纪 (AD)。他们并非祭司贵族,也不掌控圣殿,而是以律法教师、文士、经学家为主的平民宗教精英。他们的主要活动场所是会堂,而不是圣殿献祭体系。

在社会结构上,他们不是统治阶级,却拥有极高的道德与宗教权威,被普通百姓视为 “最敬虔、最懂圣经的人”。

二、他们真正追求的是什么

法利赛人并非不重视圣经,恰恰相反,他们极度重视摩西律法。问题不在于他们是否认真,而在于他们认真追求的对象发生了转移。

他们追求的不是律法作为神启示的审判与引导,而是“律法之义”——一种可以被计算、被比较、被展示的义。律法从 “显明罪、引人悔改” 的工具,变成了 “建立自义、区分他人” 的标准 (罗 9:31-32; 10:3)。

因此,他们不是被律法塑造,而是使用律法。

三、口传传统与 “生活圣殿化”

法利赛人强调除成文律法之外的口传传统,用以把律法细化到生活的每一个层面:吃什么、怎么洗手、安息日走多远、誓言如何起效。

他们的理想是把圣殿中的圣洁标准扩展到日常生活,使每个犹太人都像活在圣殿里一样。这在动机上并非虚假,但在结果上却制造了一套高度可视化、可评估的 “属灵等级”。

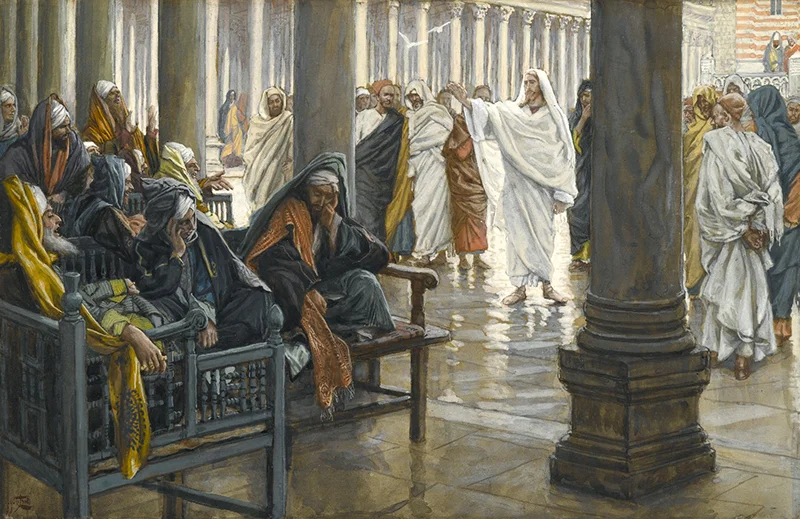

四、耶稣为何严厉责备他们

耶稣并未反对律法本身,也未否认他们的宗教认真。祂责备的是三点:

- 第一,传统高于神的诫命

他们用人的解释取代了神启示的权威 (可 7:6-13)。

- 第二,外在义掩盖内在败坏

他们追求被人看见的义,却忽略心在神面前的真实光景 (太 23:27-28)。

- 第三,拒绝律法所指向的基督

他们查考圣经,却不肯到祂这里来得生命 (约 5:39-40)。

五、常见误解需要排除

- 误解一:法利赛人都是虚伪的骗子

错误。他们大多是真诚、勤奋、自律的人。

- 误解二:耶稣反对一切律法与规范

错误。耶稣反对的是以行为建立称义根基。

- 误解三:法利赛人问题只是 “太严格”

错误。问题不是严格,而是严格所服务的目标。

六、新约中的神学定位

法利赛人代表一种典型的人类宗教倾向:

- 把神的启示转化为人的成就;

- 把顺服的果子,变成称义的根基;

- 把律法的镜子,当成自义的奖章。

因此,法利赛人不是古代特例,而是人类堕落宗教心态的集中体现。他们的失败,不是因为太认真,而是因为认真地追求了错误的义。

Default

Default  No Comments

No Comments  Default

Default  No Comments

No Comments